|

| ||||

PROJECT HISTORY by Anthony Fabian

How it all began

I first heard the story of Sandra Laing in July 2000 on BBC’s Radio 4. British journalist Peter White had gone to South Africa to interview Sandra and her testimony left me stunned. For days afterwards, I had a lump in my throat when I thought about her story and realised it had the potential to touch people around the world as a feature film. I also felt a tremendous sense of outrage that, after all she had been through, Sandra was still living in abject poverty, while her white family had prospered. I felt compelled to make some kind of reparation, and thought a film might help provide her with long-term financial security.

Development

The first step was to secure Sandra’s life-story rights. With the help of a couple of journalists in South Africa — Karien van der Merwe and Karen Le Roux — I managed to get Sandra’s neighbour’s telephone number in Tsakane township, East Rand (Sandra herself did not have a phone). I explained what I hoped to do, and asked whether she would consider

assigning her life-story rights to me. She would be paid option fees, and eventually a reasonable sum of money if the film were made. She agreed to meet me. Six weeks after I had heard

Around this time, I also conceived the notion of selling the publication rights to Sandra’s story: people kept asking me, “Is there a book?” and I realised there probably should be. I was very lucky to have got the book commissioned from the first publisher I approached: Talk Miramax Books. Miramax Films had just set up an imprint for books they thought might make interesting films, so it seemed a natural port of call. The writer of the book, Judith Stone — an American journalist based in New York, contributing editor to Oprah Magazine — was chosen to give an ‘outsider’s perspective’ on the story — which was primarily intended for an American readership, unfamiliar with South African history. The job of the book and the film is very different — one being factual, the other dramatic — and Judith Stone proved a very determined, hard working biographer, whose book, ‘When She Was White’ was finally published in April 2007, to excellent reviews. The other happy outcome of the book’s publication is that the contract I negotiated gave Sandra a generous advance and enabled her to buy her first home, in a peaceful suburb of Johannesburg. I also encouraged her to start her own business — a spaza shop in her converted garage — something sustainable. (Running a shop is in her blood, as her parents were shopkeepers.) So part of the dream was coming true: Sandra was better off, much happier and more confident in herself.

Meanwhile work began on the screenplay which was developed over several drafts written consecutively by Helena Kriel, Jessie Keyt, Helen Crawley and myself. In the meantime, I had been joined by Margaret Matheson of Bard Entertainments and Genevieve Hofmeyr of Moonlighting Films in South Africa as co-producers.

Although by then I had been to South Africa several times, had shot a one-hour documentary in Stellenbosch about the Spier Music Festival (Township Opera) — which told the story of the company that eventually made the Golden Bear-winning feature film, U-Carmen — I still felt the need to have substantial input from South Africans, in order to do the story justice. So Margaret and I persuaded the UK Film Council to fund a three week period of casting and script development workshops — using actors to improvise scenes based on a draft of the script I’d prepared before heading off to Johannesburg — so that we could test every scene and create new material. Moonlighting Films arranged the entire workshop process on the ground, with their usual, steadfast efficiency. We

Packaging

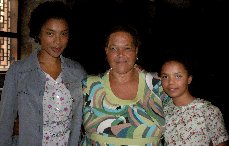

Casting director Susie Figgis has a strong relationship with South Africa (her husband was born and brought up there ) and she agreed to help us cast the stars, and eventually led us to Sophie Okonedo, who committed to playing the adult Sandra in July 2005. Sophie had just been nominated for an Oscar for Hotel Rwanda and it was quite a coup to have her attached to Skin. Not long afterwards, I met with Alice Krige — born in Uppington of Afrikaner parents and brought up in Port Elizabeth, who had made a career for herself in Hollywood. From the moment I met Alice, I felt I had come home: she fully embodied the role and I knew there was no need to look further.

In September 2006, the UK Film Council agreed to fund a ‘Pilot’ — three short scenes from the film — which we could then use as a promotional tool to attract financiers, distributors and a sales agent. Preproduction lasted three weeks and production two days — and Moonlighting pulled out all the stops to ensure we had maximum bang for our minimal bucks. The Pilot, which was post-produced in the UK, proved a very useful tool in attracting more stars and finance to the project.

In November 2006, Margaret Matheson approached the LA-based international sales agent Robbie Little, who had very successfully sold the Oscar-winning film ‘Tsotsi’, to sell SKIN. Robbie took the project to the Berlin Film Festival and achieved an encouraging number of presales, including a cornerstone sale to France’s UGC PH (Philippe Hellmann). All this arose from the strength of the script and Sophie Okonedo’s commitment to the project. The other stars — including Sam Neill — had not yet come on board. The presales subsequently gave confidence to investors such as the IDC and Aramid, who eventually financed the film.

Production

We started production in September 2007 with the usual indie movie fears of too little time, not enough money.

Our aim was to create a moving human drama that would also have an epic quality, as the story spans the turbulent final thirty years of apartheid.

The first task was to find a location that could serve as a unit base for the majority of the shoot. We had over fifty locations to cover in just forty-two days — so keeping those sets within a relatively contained area was critical if we were to have a fighting chance of shooting to schedule.

Things began well: I was taken to Remhoogte — the Laing Compound, as we renamed it — by the production designer, Billy Keam, on the first day of location scouting. Northeast of Johannesburg, about fifteen minutes from the Hartebeespoort Dam, which serves as a weekend retreat for townies, we travelled down a long, rutted road, leaving clouds of red dust in our wake. We reached the crest of a hill, at the bottom of which sat a grove of pine and eucalyptus trees surrounding a complex of single-storey buildings. The hairs went up on the back of my neck: it looked exactly like the original Laing farm, three hundred kilometres away in Mpumalanga (then known as the Eastern Transvaal) — but this location was infinitely more practical, as our crew and equipment would be coming from the big city.

What I didn’t know was that this area (where we ended up basing ourselves for the first five weeks of the shoot) has a freakish micro-climate that attracts the greatest number of electrical storms in the world. (The amount of metal in the earth is a contributing factor; a few of us were staying near a platinum mine, and our roads were paved with ore.) Thankfully, the first week of production we were spared the lightning and the rain. Then summer decided to make an early visit. The heavens opened and it seemed as though they would never stop. The Laing Compound

It wasn’t all bad. Often, the weather would hold until just after our last shot — or not come until the end of the day. At the end of our second week, there was an electrical storm so violent, with so many flashes of lightning practically licking our vehicles as we drove through in convoy, that I became convinced I’d be struck before reaching the hotel. For most of this journey, I racked my brain, trying to assign my successor — not that I would have been able to communicate my choice, had I fried to death in the car. (I was later told that one of the safest places to be in an electrical storm is a car. True or false, it was reassuring).

On another occasion, as we were attempting to finish a scene in a township, a dust and windstorm the like of which I’ve never seen began to kick up. The crew began to wrap, but our second cameraman, George Loxton, saw the sun setting magnificently over the mountains and couldn’t bear to let it disappear unrecorded: he put the camera high on the sticks, wrapped himself in a plastic sheet and, held down by his assistant, captured the massive lightning bolt that forked across the blood-red sky — a stunning bonus shot that made it into the film, before Sandra packs her belongings to leave Petrus.

Another massive challenge for the production was the sheer number of people on screen: seventy-seven speaking parts, babies of various ages (and colours), including a newborn, only twelve days old, and the hundreds — on one occasion nearly a thousand — extras we had to call on an ad hoc basis. Somehow, the production and assistant director team managed to bring, costume (and feed) all these people — including some of the finest actors South Africa has to offer — to the set every day, so that we rarely had to recast a role.

The most daunting scene for me, as a first-time feature director, was the forced removal scene, which involved hundreds of extras, animals (goats, dogs and chickens) period bulldozers, general mayhem and destruction, and a collapsible set... But the skill of the cameraman, Dewald Aukema — who suggested we use as much special fx smoke as possible, to add to the confusion — and the efficiency of the highly experienced First AD, Mary Soan, who marshalled the extras — made it possible for us to film the entire sequence in just a day and a half. (It was scheduled for one day, but naturally the heavens opened in the middle of the afternoon, and we had to complete the scene the following day).

It now feels like something of a miracle that, despite all the challenges posed by the number of locations, the large cast and the crazy weather, we managed to finish the film pretty much on time and on budget — and survived to tell the tale.